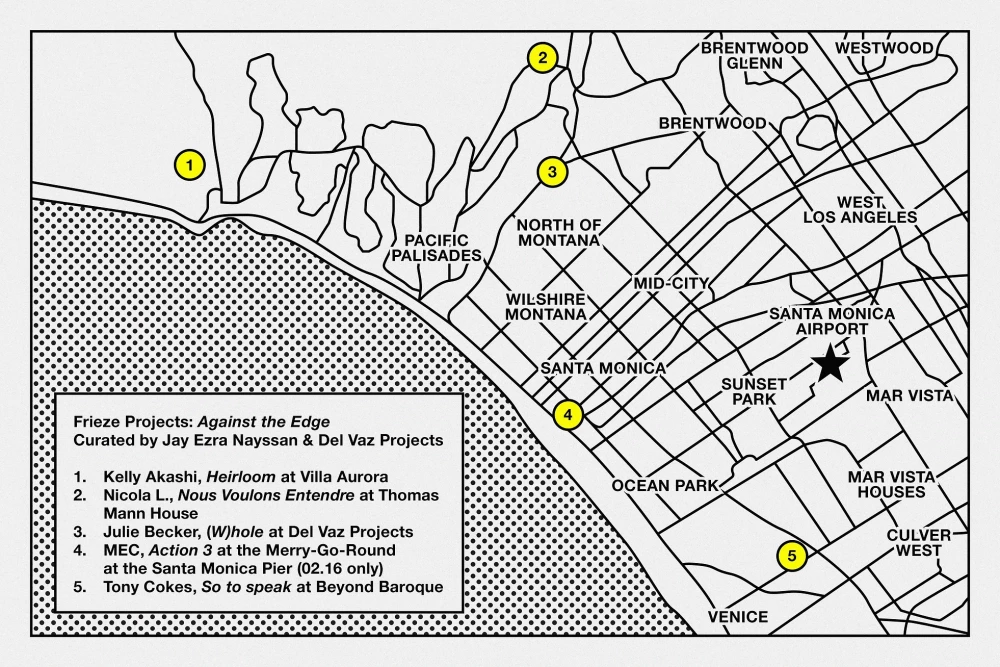

Frieze Projects: Against The Edge

This project takes its name from an interview between artists Fritz Haeg and Doug Aitken in Aitken’s book The Idea of the West. In a collection of 1,000 interviews conducted by Doug asking friends and colleagues “What is your idea of the West?”, Fritz responded: “To the American psyche: west equals movement, more space, resources, freedom... For those of us that do occupy this slim line along the Pacific coast, we have a unique sense of limits. For everyone else there’s a vague sense of: no matter how much of a mess we're making here, there's more that way. But for us living against the edge, it’s like, ‘No, this is it. There's nowhere else to go.’”

This year, Frieze is continuing its move west from Hollywood and Beverly Hills to Santa Monica, settling in arguably one of the most multifaceted urban complexes in west Los Angeles: the Santa Monica Municipal Airport. The SMMA is a prime example of the multi-purposing of public sites that takes place in the rapid, often uncontrolled, evolution this city has undergone in the last century. Established in 1917 as the home of the Douglas Aircraft Co., the site currently operates not only as an airport (you might recall Harrison Ford crashed his plane on a nearby golf course shortly after taking off from there), but also as a public park with soccer field, a film set, entertainment venue, and a satellite campus for Santa Monica College’s ceramics program.

I know this airport well because I used to drive through it as a shortcut to get from my apartment in Sawtelle to Liz Craft and Pentti Monkkonen’s house, where they used to host exhibitions at Paradise Garage. Beginning in 2012, the garage-cum-gallery shed in the artists’ backyard hosted a number of exhibitions until Oscar Tuazon collapsed the structure in one fell swoop in a work called This won’t take long (2015). This marked the end of Paradise Garage. Liz and Pentti closed the gallery project in order to begin the renovation of their home and studio, but then left Los Angeles for New York and Berlin a few years later and haven’t really come back. There are only a few galleries left here west of the 405 – L.A. Louver, 5 Car Garage, and Le Maximum, and of course the Getty (Center and Villa), and the 18th Street Art Center, which used to be home to the Santa Monica Museum of Art until it relocated to Downtown in 2017 and became the Institute of Contemporary Art L.A.… The Westside has, in recent years, begun to feel a bit marginal to the pull of Los Angeles’ more weighty centers of art.

Because I grew up here and currently operate Del Vaz Projects out of my home in Santa Monica, I was invited by Frieze’s director Christine Messineo to curate a series of artist’s projects, installations, performances, and talks along the coastal Westside in response to the fair’s move (further) west. I took this opportunity to revisit some of my favorite texts on the City of Los Angeles at large, including Mike Davis’s City of Quartz, Norman Klein’s History of Forgetting, Chris Kraus’s Video Green, Peter Plagen’s Ecology of Evil, and Jean Stein’s West of Eden. I was inspired by Norman Klein’s “anti-tours” where, as a professor at Cal Arts, he would take his students to vacant sites that, because of L.A.’s tendency to erase memory, no longer exist: “a movie studio, a whorehouse, whatever.” The buildings had been demolished, Klein explains, because of L.A.’s penchant for self-erasure. Thom Anderson got it all wrong—L.A. doesn’t play itself, it forgets itself.

The sites that host Against the Edge, though, actually still exist. And their stories haven’t necessarily been erased or forgotten. They just haven’t really been shared. And that’s what provided me with the perfect theater to propose some new and imagined relationships between site and artist, history and fiction. Taking a cue from Jean Stein’s skill for recording oral history and joshing with its factual faultiness, I’ve used these imago-sites as an opportunity to mix history, urban myth, anecdote, and personal memory to create a story of not only what’s gone, but what’s left. Although a fraction of the community and cultural centers it once contained, there remains an incredibly vibrant constellation of culturally significant sites along the coastal Westside which have been and remain integral to the history of modern and contemporary art in Los Angeles. This is my anti-tour, my love letter to the Westside. This is also its swan song.

What began as a chain of artist colonies, entertainment districts, and laborer’s communities along the coast of west Los Angeles, the City of Santa Monica and neighboring communities of Venice Beach and Pacific Palisades have, with the help of real estate speculation and short-sighted urbanization plans, essentially “flipped” on themselves, making it inaccessible to creative communities like those that once found refuge on this side of a White Wall that was built by Downtown elites in the first half of the twentieth century. The truth is, art actually fuels that speculation, and even foreshadow it – in 1967 Ed Ruscha aerially photographed thirty-four parking lots; in 2011 he was forced out of his Venice Beach studio after twenty-six years because the City of L.A. was converting a railroad easement between Abbot Kinney and Electric Ave into a parking lot, probably for Gjelina and Intelligentsia Coffee customers.