Raymie Iadevaia: Hereafter

The Pit is delighted to announce “Hereafter,” a solo exhibition with Los Angeles based artist Raymie Iadevaia. His second exhibition with the gallery, the show will be on view from September 24 - October 31, 2024 with an artist reception on Saturday, September 28th from 5-7pm alongside Joel Gaitan and Kirk Mangus respective solo shows.

“The search for metaphor, the weight of doleful contradiction; these tell you exactly where you are.”

—Elizabeth Hardwick

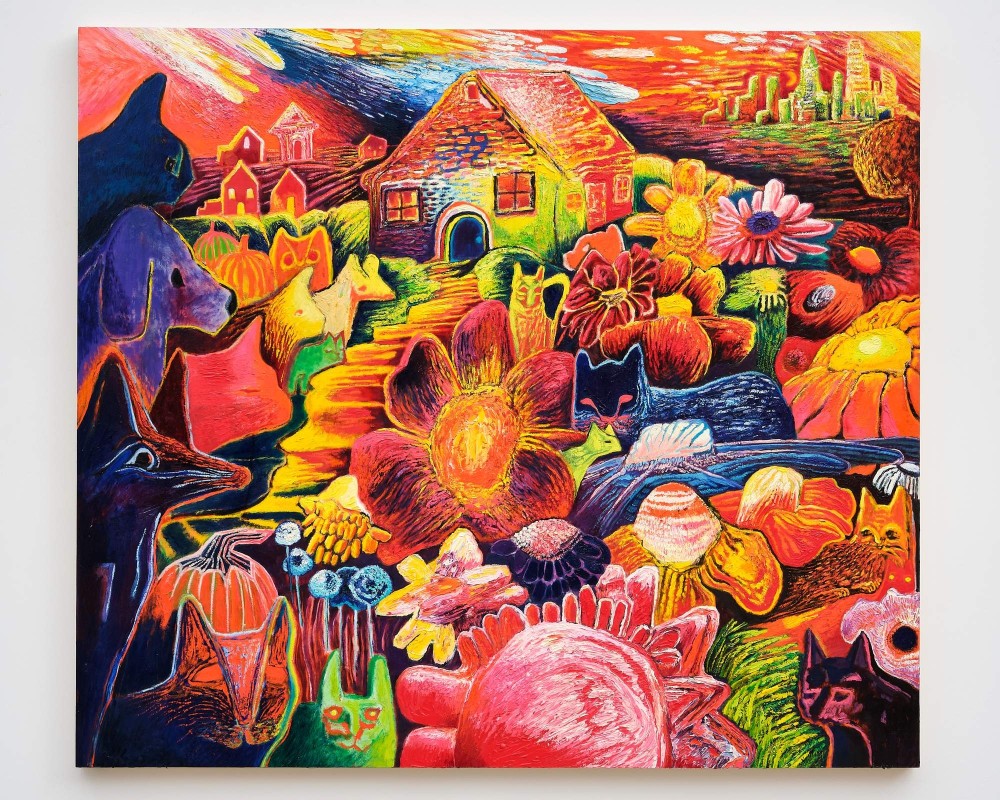

Luminosity, voluminous space saturated by light, a brightness that blinds, and still manages to be seen, like Milton’s ‘darkness visible,’ but overturned—seen in reverse. In Raymie Iadevaia’s “Hereafter,” lightness is marked by its loss, and only-ever glimpsed in passing, in the penumbra of painterly aporia. It comes intimated that painting moves us to glimpse what floats in the impasses of its own language: its irresolvable contradictions, and disjunctions, its internal discord. An obvious route into the works’ world-build would be to cite the psychedelic; though, that doesn’t feel quite right. Still, something slipping under reason’s radar turns us to see things differently, as if turning sight backwards into the dark, enticing not to see, per seeking truth in representation, but to grasp all that appears as visible. It’s all textures, tilting view, all things (cloud castles and water currents, meteor storms, and watchful creatures) made motionlessly unstable in their own excess. The multitude of expressions make present the empathetic as a form of discord, as implied in the German word for empathy, signifying something assuming the shape of another’s feelings. Everything is drawn into a kind of sameness, alighting on destinies linked by a likeness, by co-occurrence, by common resonances.

And, I am also thinking about discord, as in the ‘discordant,’ from dis- (a negation, reversal) & cor, cord- ‘heart.’ Maurice Blanchot says, at the end of The Writing of the Disaster, “The written word: in it we no longer live. Not that it announces: “Yesterday it was over.” But it is our discord, the gift of the word which is precarious.” If, as Blanchot goes on to intimate, eternity becomes transitory in what remains to be said, and what remains to be said is assumed as an afterlife of sorts, i.e., the ‘hereafter;’ then perhaps Iadevaia’s process could be said to move into the space of discord to trace the invisible remains of mental pictures, past impressions, and other fleeting images that pass through a life. In other words, he’s chasing the afterglow or radiance of things that touch us. To this end, nothing ever really ends, but is always available to be revised, revisited. Something is reversed at heart, here, and given to us as image. It goes to show just how ablaze the mind can be—how emotions can seem so swindling, memories so warped by outside forces, and thought, in its ceaseless momentum, such a necessary break.

“Thinking is drawn,” as Norman Malcolm once wrote, arguing for meaning as a precondition of syntax, “against the background of the form of the world.” Iadevaia’s landscapes contour the uncanny of what was lost into the basements of memory, here backlit by an allusive radiance, as lines, linked in correspondent gestures, forms seeking sameness, and colors, courting psychic disarray, move us to sense expressive limits. Think, for example, to the projective valence of the backgrounds in Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) if all its characters were removed. Drawn into view would be an atmosphere wrought in allusive motion, forced perspectives, and impossible scales, like pushing feelings of vertigo in aerial views straight into a canyon, or clouds of daisies ballooning a meadow to the scale of the imagination. In Iadevaia’s allusive landscapes, blown-up, made to glow, and shift are those details, the minutiae of an everyday life, which affix to mind most particularly—and strangely—in moments of total psychic transformation, where everything in the mind seems to have changed, yet everything else around appears completely intact.

Some might say, it’s the unconscious drifting forward, like automatisms drawn as squiggles and shapes in the margins of notepads. Still, I think of Iadevaia less as vested in psychic mechanisms that spill over and out, than someone paying due attention to all that’s left in the margins of experience. Questions left unasked, details overlooked, psychic weather never mentioned. Iadevaia’s paintings, in this sense, make literal the inexpressible background that foregrounds all meaning. The ‘hereafter,’ in this sense, courts the aporetic as a state of loss, which contrary to one’s expectations, is rarely a pure void, but a space (here) that fills to the brim (after.) Questions and conflicting emotions, hermeneutic knots and missed moments, memories lost and recovered, conversations recounted, images redrawn from the mind. These are sites swirling in the chaos of transformative loss—in the invisible that remains to be said, shown.

– Sabrina Tarasoff