SHERRILL ROLAND: DO WITHOUT, DO WITHIN

Sherrill Roland’s interdisciplinary practice deals with concepts of innocence, racial ontology, and community; reimagining their social and political implications in the context of the American criminal justice system. For more than three years, Roland's right to self-determination was lost to a wrongful incarceration. After spending ten months in prison for a crime he was later exonerated for, he returned to his artistic practice, converting the haunting nuances of the surrounding aesthetics into new sculptural works, installations, and prints. Roland shares his story and creates space for others to do the same, illuminating the invisible costs, damages, and burdens of incarceration.

do without, do within features five new bodies of work, which explore intense longing under physical and psychological constraint, and the inner strength required to sustain self-hood, under insurmountable circumstances. Throughout this exhibition, Roland is recalling forms of desperation, as a witness, internally within himself and upon others. What we see in others reflects our own capacities, and possible incapacities. Can you imagine yourself inhabiting space when right and wrong coincide?

On view in the main gallery are three sculptures of double-headed fans with slowly turning blades. Inspired by a specific moment during Roland’s incarceration when the HVAC system in his housing unit broke down in the middle of summer heat wave, he recalls how fellow incarcerated individuals came together to protest the unbearable conditions by refusing to return to their cells. As a compromise, one oscillating fan was provided for each tier, offering minimal to no relief. Cooling air could only be received through the mail slots of their cell doors when locked in the cells. Each night, individuals would turn off the oscillating function by roughly turning the heads of the fan to face them, causing the fans to break down. Eventually, the fans were taken away so they couldn’t be fashioned into weapons. In the Conflict Resolution works, Roland has joined two fan heads together, representing the duality of the fans in prison as objects of necessity as well as potential harm. The blades of the fans are carved into sharpened forms, which invite further danger through the rectangular cutouts in the fan cage.

Also on view are four pairs of wall-mounted sculptures made of cotton, concrete and steel. Shaped like domino tiles, the Boneyard diptychs resemble the Brutalist architecture of prisons. Roland read a Bible passage (Ezekiel 37:1-14) recounting the story of the valley of dry bones, which are without life and spirit, and how they are brought back to life. Struck by the parallels to incarcerated individuals, piled high and anonymous in number, they are also experiencing a lack of hope and are in desperate need of a resurrecting force that makes them whole again.

Roland’s new Thirsties works, which are also on view in the main gallery, continue his use of Kool-Aid as material, the colorful beverage commonly served in prison. The etched acrylic wall sculptures are filled with Kool-Aid mixed with resin and depict the dotted pattern seen in the Ishihara Test, a color vision test for detection of red-green color deficiencies using pseudoisochromatic plates. Each plate depicts a solid circle of colored dots appearing randomized in color and size. Within the pattern are dots which form a shape clearly visible to those with normal color vision, and invisible, or difficult to see to those with a red-green color vision defect. In Roland’s work, a single color depicts the shape of the tongue of the iconic Thirsties, the minions of the Kool-Aid Man’s archnemesis in the Marvel Comics, which are dispatched to cause thirst. The visibility — or for some, the invisibility — of the Thirsties is a reminder that not all experiences are recognizable to others.

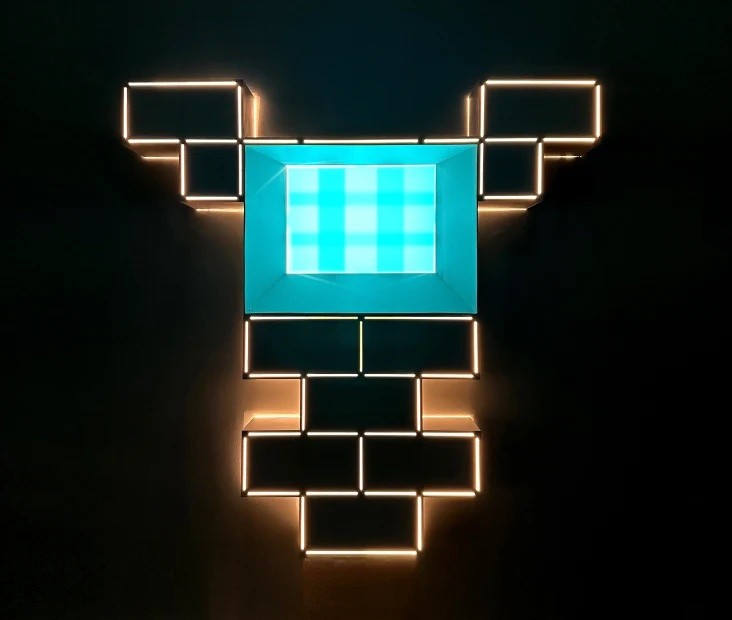

Two new lightboxes in the rear gallery resemble the structure of a window embedded within the cinder blocks of a prison cell. Positioned just out of reach, the inoperable window functions more as an architectural reminder of civilian life that existed beyond. Reminiscent of the glowing crosses on the hillsides of Western North Carolina, the Forecast works invoke Roland's practice of prayer toward their neon sustenance.

In the front gallery, Roland has created a series of six prints based on an article from the Associated Press published in his local Asheville newspaper in the late 1990s about California’s inmate firefighter program. Shaped like flags, the prints incorporate red Kool-Aid, indicative of the warm glow of fire, and embossed varnish, symbolizing dimensions of smoke. Here Roland makes explicit the extremity despair that incarceration produces, prompting inmates to choose potentially fatal work over penal time in prison. Fighting fires becomes a path to freedom. For these works, Roland studied the California carceral system’s relationship to the inmate firefighter program, which began in 1946 and is still active today. Through this initiative, prisoners opt to undertake dangerous, grueling work as first responders and rescuers to battle wildfires throughout the state. As the fires have grown increasingly prevalent since the program’s inception, they are still paid minimally for their service. In this exhibition, Roland posits the conception “trial by fire,” an effort to burn away the public’s perception of guilt through enacting the role of heroism.

Born in 1984 in Asheville, North Carolina, Sherrill Roland studied at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2018) and earned his MFA and BFA from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (2017 and 2009). He has had solo exhibitions at the Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, NC (2022-2023); Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA), Winston-Salem, NC (2022); Shirley Fiterman Art Center, Borough of Manhattan Community College, New York (2019); Maria & Alberto de la Cruz Gallery, Georgetown University, Washington, DC (2019); Brooklyn Public Library (Central Library), Brooklyn, NY (2017); Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles (2017); among others. His work has been included in group exhibitions at Ford Foundation Gallery, New York (2023); The Warehouse, Dallas, TX (2022); Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, Durham, NC (2021); Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, Asheville, NC (2021); San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA (2020); Tufts University Art Galleries, Medford, MA (2020); Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA (2019); CAM Houston, Houston (2018); and Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2017). Roland is the recipient of the Creative Capital Award (2021); South Arts Southern Grand Prize & State Fellowship (2020); and was an Art for Justice Grantee (2020) in addition to many other awards and recognitions. Roland’s work is the permanent collections of the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA; Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, NC; Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC; North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC; Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; Fountainhead, Miami; and Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Arts + Culture, Charlotte, NC. He lives and works in Durham, NC.