Frieze Los Angeles Booth D7

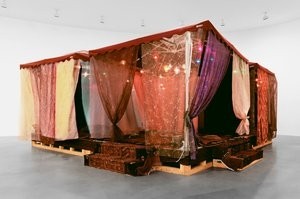

Gagosian is pleased to announce its participation in Frieze Los Angeles 2025 with Nomadic Folly (2001), an enveloping large-scale installation by Chris Burden that was produced for the seventh Istanbul Biennial, incorporating locally sourced materials and objects. This is the first time that the work has been exhibited in the United States. At a profoundly difficult moment for the city of Los Angeles, this project by one of its greatest artists—perhaps his gentlest and most humanistic—offers visitors a place to gather in safety and community.

In challenging times, art can provide a place for escape, for joy, and for community. Chris Burden’s Nomadic Folly (2001), Gagosian’s featured solo presentation for Frieze Los Angeles 2025, offers all of these things.

While this marks the first time Nomadic Folly has ever been shown in the United States, the work—a large-format, interactive sculptural installation—was initially created by Burden for the seventh Istanbul Biennial, which opened on September 21, 2001. When the California-based artist arrived in Turkey, he only had drawings and preliminary plans for Nomadic Folly, which would be constructed on-site in the courtyard of the eighteenth-century Imperial Mint at Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace. Leaving behind the enormous destruction from the terrorist attacks that took place in the United States on September 11, 2001, not three weeks earlier, Burden immersed himself in the profound beauty of Middle Eastern culture. He sourced all of his materials from local souks to produce a work that the artist described as “an oasis of beauty,” one that exists as a reprieve within a world otherwise undone.

In the wake of the devastating fires in Los Angeles in early 2025, Gagosian returns to Burden’s ambitions of creating art that can bring people together. Nomadic Folly is composed of a twenty-square-foot wood platform, upon which the artist has built an architectural folly inspired by Turkish culture and history. Using umbrellas, silken fabrics, and braided ropes, Burden constructed four interior “rooms,” each decorated with soft pillows, plush rugs, and glass and metal hanging lamps; it is accompanied by a selection of traditional Middle Eastern music that plays continuously. The artist’s intention, which is maintained in Gagosian’s booth at Frieze Los Angeles, is for visitors to remove their shoes before entry and linger in the warmth of the tranquil, dreamlike setting. Both then, in 2001, and now, Nomadic Folly demonstrates art’s ability to offer a space for contemplation.

Burden presents a multisensory experience for the viewer, one carefully crafted to transform sight, sound, and touch and encourage human interaction. Surrounded by diaphanous fabrics in jewellike shades of aquamarine, brown topaz, amethyst, garnet, and ruby, the audience is meant to find respite as reality quite literally dissolves from view. The music transports one’s imagination to far-off places and times, while the textures of the fabrics arouse unique bodily sensations. What emerges is a transportive site of visual opulence and social conviviality, where the act of coming together with others might serve as the foundation for building something new, even maybe joyous, from life’s exigencies.

As one of Los Angeles’s most celebrated and well-known artists, Burden produced what is arguably the city’s most iconic works of public art. Urban Light (2008), his magnificent installation of 202 powder-coated vintage streetlamps arranged into a series of rows, forms a temple of light at the entrance of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Like Nomadic Folly, this later work draws upon architecture of the past—in this case, ancient Roman colonnades—to inspire optimism for the future based on a celebration of humanity’s historical achievements and the greatness that is possible when we come together as one.

Nomadic Folly relates to Burden’s long-standing engagement with architecture and urbanism, both of which recur in various forms throughout his career. Whether towering skyscrapers built from stainless-steel reproductions of children’s building toys such as Erector and Meccano sets, or the creation of miniature cities populated with building types from around the globe, Burden has continually probed the relationship between architecture and art. He had initially planned to pursue a career as an architect; however, Pomona College, where he completed his undergraduate studies, did not offer a dedicated BFA degree in the field. Instead, Burden took classes in physics and art. After completing a series of summer internships at architectural firms, he switched tracks, citing the slow progression in architecture from apprentice to being able to execute one’s vision. Sculpture seemed to offer his desired scale and ambition, without the time lag; he noted in a 2003 lecture at the Southern California Institute of Architecture that “in sculpture, I could get something done right away.”

In architecture, the term “folly” describes a decorative, and often temporary, structure, which frequently alludes in style to existing building types or conventional motifs. Most famously found in English gardens, follies have no practical purpose other than providing aesthetic enjoyment and a site of relaxation. This sense of playful whimsy is evident as well in other sculptural interventions or sculptures by Burden, such as Wexner Castle (1990), which saw the artist altering the façade of Peter Eisenman’s building designed for the Wexner Center for the Visual Arts in Columbus, Ohio, with medieval architectural features such as crenellations, or La Tour des Trois Museaux (1994), in which Burden erected a faux thirteenth-century stone fortress from pieces of foam and wood.

Both unique and emblematic of Burden’s remarkable artistic practice, Nomadic Folly is one of only two follies that the artist created in his lifetime. It predates Dreamer’s Folly, which was made in 2010. This later piece represented a more permanent structure, being built from the bases of streetlamps; notably, both works were shown together at Gagosian’s Rome gallery in Burden’s 2010 exhibition The Heart: Open or Closed, which explored themes of humanity’s capacity for hate and tolerance.

In the context of ongoing relief efforts to support the city of Los Angeles, Gagosian is participating in the LA Arts Community Fire Relief Fund. Led by the J. Paul Getty Trust, with support from a coalition of major arts organizations and philanthropists, the fund provides critical emergency support for artists and art workers impacted by the fire.