Alex Israel: Noir

An LA artist who doesn’t reckon with noir is a flickering bulb that lures no moths, and maybe no bulb at all. So I was glad to hear that Alex Israel, who was born and grew up here, who lives and works and belongs here, was doing the native reckoning where else but Warner Bros., or what’s left of it, where John Huston and Humphrey Bogart (and Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet) made The Maltese Falcon for six summer weeks of 1941. If anyone called it the first noir, I wouldn’t fight them.

Some say noir is a genre, to which I would argue, there are noir musicals; others have said, with better evidence, that noir is a style, but it takes more than shadowed light through venetian blinds to do the dirty deed. I’ve heard it said that noir is a mood: doom, but Titanic (1997) is no Criss Cross (1949).

Like the filmmakers before him, Israel is defining the noir tendency in his own way, through images. These are painted streetscapes. They began, though, as photos and sketches, visual ideas that Israel enhanced with reference material—the purplish-blue gradients he wanted for the night sky, for instance, or specific Mexican fan palm silhouettes to dot their horizons—in order to create blueprints for what would become at first digital renderings, and then ultimately finished paintings. Beginning in 2021, these blueprints went back and forth between Israel and a pair of animators. Years of additions and subtractions produced renderings that were then painted in acrylic on canvas by an artist in the Scenic Art department at Warner Bros.

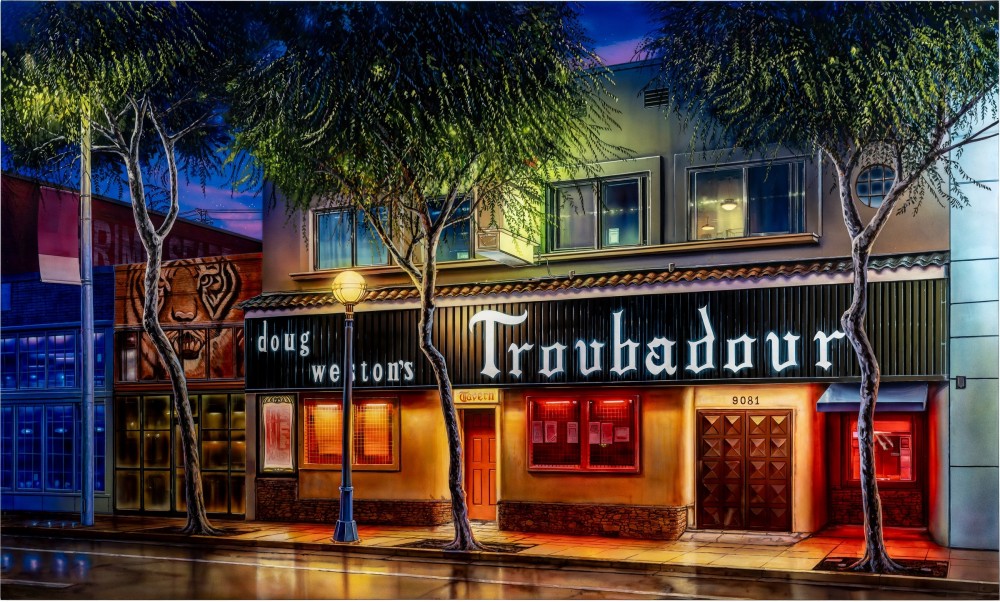

Upon first seeing the works in a warehouse-like space on the edge of the Burbank backlot, I was home. The Troubadour, the Cadillac dealership in the Valley, the Bruin Theater in Westwood . . . The combination of their CinemaScope proportions and my memory—our memory, if you’re one of ours—put me there in the virtual reality of a beloved present/past. Or is it “past/present”? The locations Israel picked for his pictures are undeniably of their time—the 1940s car dealership, the ’50s diner, the ’60s gas station, the ’70s lingerie shop, the ’80s yogurt spot—but still a part of the present. When you add to that your own memories, the temporal effect on the brain is kaleidoscopic. Not where am I, but when am I?

There are no people, only mannequins, in a lingerie shop window, no cars except behind glass in a Van Nuys showroom all done up for Christmas. I wouldn’t say it’s a nightmare, but it’s certainly some kind of a dream, like one of those video games where the player— whose “crime” is unknown, and whose mystery is their past—wakes up somewhere strange and has to figure out how they got there. And this feeling is essential to the thing we call “noir,” the haunting that crept into Hollywood with World War II, its visual and psychological disorientations of time and space, the cinematic analogues to a modern world suddenly unmoored.

If Israel’s pictures are seductive, they should be. Femmes wouldn’t be fatales if they weren’t. The paintings’ rich, pulpy candy colors and nostalgic lure, their slick, sensual surfaces that say come hither . . . these are not the girls next door. Something of this duplicity, the uncanny appeal of each building’s façade, is conscientiously layered into Israel’s process. The photographs and references of Israel’s blueprints are not retouched but redrawn, and in this redrawing they are heightened by local myth and redescribed through the lens of Israel’s memory in dramatic, theatrical lighting and exaggerated, impossible perspective. These places only seem natural. They are to be loved, but not trusted.

And those who love Los Angeles share Israel’s view that our city can be beautified by illusions. We know that “Hollywood Liquor”—to borrow from a cheery, brightly lit sign on Israel’s Hollywood Boulevard—is better than no liquor at all, and that those who don’t dream don’t know they’re already dead. Look at Israel’s skies: it’s night, yes, but what a night.

Text by Sam Wasson, from an essay to be published in the Spring 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly

This exhibition was originally scheduled to open on January 9, 2025, but was postponed due to the wildfires in the Greater Los Angeles area.

A portion of sale proceeds from Alex Israel: Noir will be donated to the LA Arts Community Fire Relief Fund. Led by the J. Paul Getty Trust, the fund provides critical emergency support for artists and arts workers impacted by the fire.

Alex Israel explores and embraces pop culture as a global visual language. Deeply entwined with his hometown of Los Angeles, he traffics in the detritus of Hollywood film production—backdrops, sets, and props—while also inhabiting the roles of filmmaker, talk-show host, designer, and hologram. Israel’s art practice doubles as a brand, centered around a Southern Californian millennial lifestyle for which his iconic profile-in-shades Self-Portrait functions as a logo, mobilized across high-visibility platforms in the worlds of art, entertainment, fashion, and tech. Embedded within each of Israel’s endeavors are not only a landscape (of LA) and a portrait (of himself), but a savvy meditation on a world fueled by celebrity, product placement, and online influence.

Israel received a BA from Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, in 2003, and an MFA from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in 2010. The following year, he began producing works at the Warner Bros. Design Studio in Burbank, California. These include Flats, a series of shaped panels airbrushed to suggest the distinctive gradients of LA sunsets, and Sky Backdrops, ethereal canvases depicting cloudy skies streaked with pink, blue, and orange. These series were born out of the set of As It Lays, a DIY talk show in which a deadpan Israel interviews celebrities about their everyday lives and routines as a form of portraiture. Israel’s Self-Portrait series began life as the show’s Hitchcock-inspired logo, evolving into color-block paintings on fiberglass panels, and ultimately into larger photorealistic paintings that feature the LA landscape, reflections on its culture industry, and clues to the artist’s process.