Marie Cosindas : Polaroid Palette

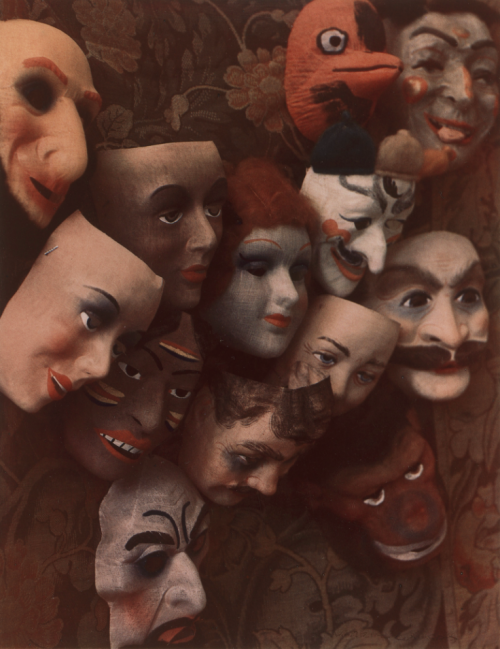

Bel Ami presents seven photographs by Marie Cosindas (1923 – 2017) from 1966, the pivotal moment in her career when she made a name for herself as a pioneer in color photography. This assortment, with their satiny hues and soft edges that seem more like oil on canvas than oozy snap-and-peel Polaroids, both satisfy and defy expectations. From an assemblage of Victorian dolls, to a pair of lounging sailors, to the half-smile of a child with pink roses on her head, to the timeless elegant woman relaxing, these photos are not what they seem. They are both old and new, high and low, slow to stage but quick to snap, luxurious and accessible. According to Tom Wolfe in the 1978 monograph Marie Cosindas: Color Photographs, Cosindas’ pictures are “like forbidden fruit unaccountably made available.”

Marie Cosindas is an exquisite slice of history, and one that has almost been forgotten. Cosindas, working under Ansel Adams in the 1960s, was made famous by her vibrant experiments commissioned by Polaroid: still-lifes and portraits which teeter-tottered between traditional forms and a radical re-envisioning, blurring the line between what could be achieved with a paintbrush and a camera. She was the fifth woman and only the second photographer working in color to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1966. The curator John Szarkowski wrote in the exhibition press release, “The photographs of Marie Cosindas are as real and as unlikely as butterflies. Their delicate otherworldliness refers to a place and time not quite identifiable.” Her achievements with color were like nothing any had seen, and there hasn’t been anything quite like them since. Why has the art world failed to give Cosindas the recognition she so richly deserves? Lisa Hostetler suggests in Aperture after Cosindas’ death in June of 2017, “Perhaps it’s because her work has always been an anomaly.”

Cosindas stood out from the crowd, and maybe it was this tendency that made her famous in the first place, at a time when few female artists were seriously regarded. In his whimsical tribute to the artist after she died at the age of 93, Tom Wolfe writes: “Marie Cosindas was barely four-foot-eleven up on her tiptoes… She was so soft-spoken that if you were eating a potato chip or even a Stoned Wheat Thin, you couldn’t make out a word she said. And inside all that delicate wrapping was an iron rod.”

She grew up in a two-room tenement apartment in Boston’s South End, one of ten children in a large Greek family. She came from poverty, yet in her heyday her famous photos would evoke the traditional oils of upper-crust drawing rooms, conjured paradoxically by a trending mass-marketed technology available to one and all. Demure yet determined, she began as an Impressionist painter “with next-to-no success,” according to Wolfe, and then turned to photography. When Ansel Adams first rejected her from his workshop, she inundated him with ladylike calls and letters from Boston until he let her in. With his help, she became one of twelve photographers chosen to dabble in Dr. Edwin Land’s invention of instant color photography. Pricked-on by her intuition, but with little technical knowledge, under a black hood she used an old-fashioned box camera to capture portraits of friends and celebrities with the new instant film. Her process – which could include dressing up her subjects, taping colored gels over the lens, or turning up the temperature in the room – was surprisingly time-consuming, producing snapshots or prints as large as a wall. Her saturated, melting tones set the standards for the dozens of glossies that reproduced her work, yet their richness has never truly been duplicated. After she got famous, she enjoyed a ride in limousine, almost as much as she enjoyed gossiping about “the famous nobs” with her less well-off friends. A fashionable renegade, Cosindas couldn’t be pinned down, classified or stereotyped, and as a female artist succeeding against the odds, this allowed her to be seen and her work to be appreciated, at least for a time.

She continued to be an anomaly. Her work became part of the historic debate about whether or not photography could be considered “a high art,” and yet critics disagreed about whether her photos made the point or proved that it was not. When back problems and follow-up surgeries prevented her from working, and the dreams and demands of the art marketplace rushed on, Marie Cosindas and her sumptuous Polaroid prints were almost forgotten.

But not quite. Wolfe writes, “When the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth mounted a major retrospective in 2013, it was a return from oblivion. She was 89 years old.” Four years later, she died. Her work remains enticingly enigmatic. Was Cosindas “one of America’s leading art photographers – or was it leading classical painters? You could choose either one, or both, and not be wrong.” What no one can dispute is the stunning results of her experiments that pushed a new technology beyond its limits. “Marie Cosindas uses the Polaroid color, which is a very beautiful color, with more pigment than otherwise,” her mentor Ansel Adams remarked. “She’s achieved some perfectly beautiful effects.”

Marie Cosindas (b. 1923, d. 2017, Boston) studied at the Modern School of Fashion Design and attended evening drawing and painting classes at the Boston Museum School. In 2013 Cosindas was the subject of a retrospective at the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth. In addition to her first two solo shows at MoMA and the MFA Boston in 1966, and her inclusion in John Szarkowski’s 1978 landmark exhibition Mirrors and Windows at MoMA, other major exhibitions of her work have been held at The Art Institute of Chicago; the International Center of Photography, New York; and the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. Her work is represented in prominent collections including George Eastman House, Rochester, NY; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; and The Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.