Between Rooms and Streets: Two Downtown Exhibitions

On Saturday, October 25, GALA organized DTLArts day: 17 galleries participated by extending their hours, organizing events and pop ups. A shuttle ran between Imperial St and Traction Ave, stopping six times at gallery hotspots along the way. The city felt intimate that afternoon, its streets and galleries blending into one moving exhibition as visitors hopped on and off the shuttle. What follows are brief accounts of the exhibitions currently on view at two participating galleries: Baert Gallery and Luis de Jesus.

CHEUNG TSZ HIN at BAERT GALLERY

I was at Baert Gallery on the opening night of a sunbeam lent to us too briefly, a show of paintings by Hong Kong-based artist Cheung Tsz Hin.

When I walked in, I was completely caught by homes of void, a substantial canvas that looks like it’s smoldering from within. Big licks of yellow and orange sweep across fragments of a surreal room—a beanbag slouched in the corner, a standing keyboard in the back, a table, slouchy leather chairs, a hanging lamp whose beams seem to spill across the floor like rippling silk. It’s the kind of painting that overwhelms your peripheral vision, the kind you can fall into through any small corner or flicker of light.

I found Hin standing nearby and asked him about it. He told me that he never plans out a canvas. He lays down a thin layer of oil paint and goes from there: “As you can see, the yellowish or greenish one is the first layer…my practice is spending lots of time looking at the canvas to find out what emotions it can bring me. When I look at the greenish yellow of the first layer, I think about some homes and places that I stayed in before…which I have since left. I start to put these feelings or emotions into the painting and add layers on it. There are multiple homes or places…in this painting.” For Hin, the canvas is a kind of layered memory palace, part past and part present. For me, it was that beanbag in the corner—a place I could sink into for a while.

We moved to a neighboring wall to look at veil on juxtaposed scenes, a smaller, stranger painting than homes of void. Before meeting Hin, I stood in front of it trying to decode the image—to me, it looked like a cluster of ghostly birch trunks ruptured by pockets of black vacuum, each void threatening to expand until it swallowed the entire scene. Hin, though, didn’t assign it any literal form. He only offered the memory that guided him: a period in university when he was suffering the loss of a family member–the dark color had brought that time back to him. “The canvas and my memory is like a feedback loop.” He said, “When I work a little bit…the Canvas will feed back a little bit to me, and somehow it can help me to reorganize how I think about or how I feel about my past. And, yeah, I think it's like a thinking tool or diary for me.”

Hin had taken the shuttle earlier that day for DTLArts Day, moving through downtown and seeing other shows. When I asked him about the coolest thing he saw, he mentioned a video work at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles: Samar Al Summary’s essay film What Goes Up (2024). It is a haunting meditation on homesickness and loss—disembodied voices narrate stories and images that fold into the desert sky. See it for yourself: Excavating the Sky will be on view at ICA LA until March 2026.

And a sunbeam lent to us too briefly remains at Baert Gallery until December 13, 2025.

JOHN M. VALADEZ at LUIS DE JESUS GALLERY

A week later, I was at Luis de Jesus on the opening night of A Two Second Gaze–Street Photography from the 1970s and 80s, an exhibition of photographs by OG Los Angeles artist, John M. Valadez.

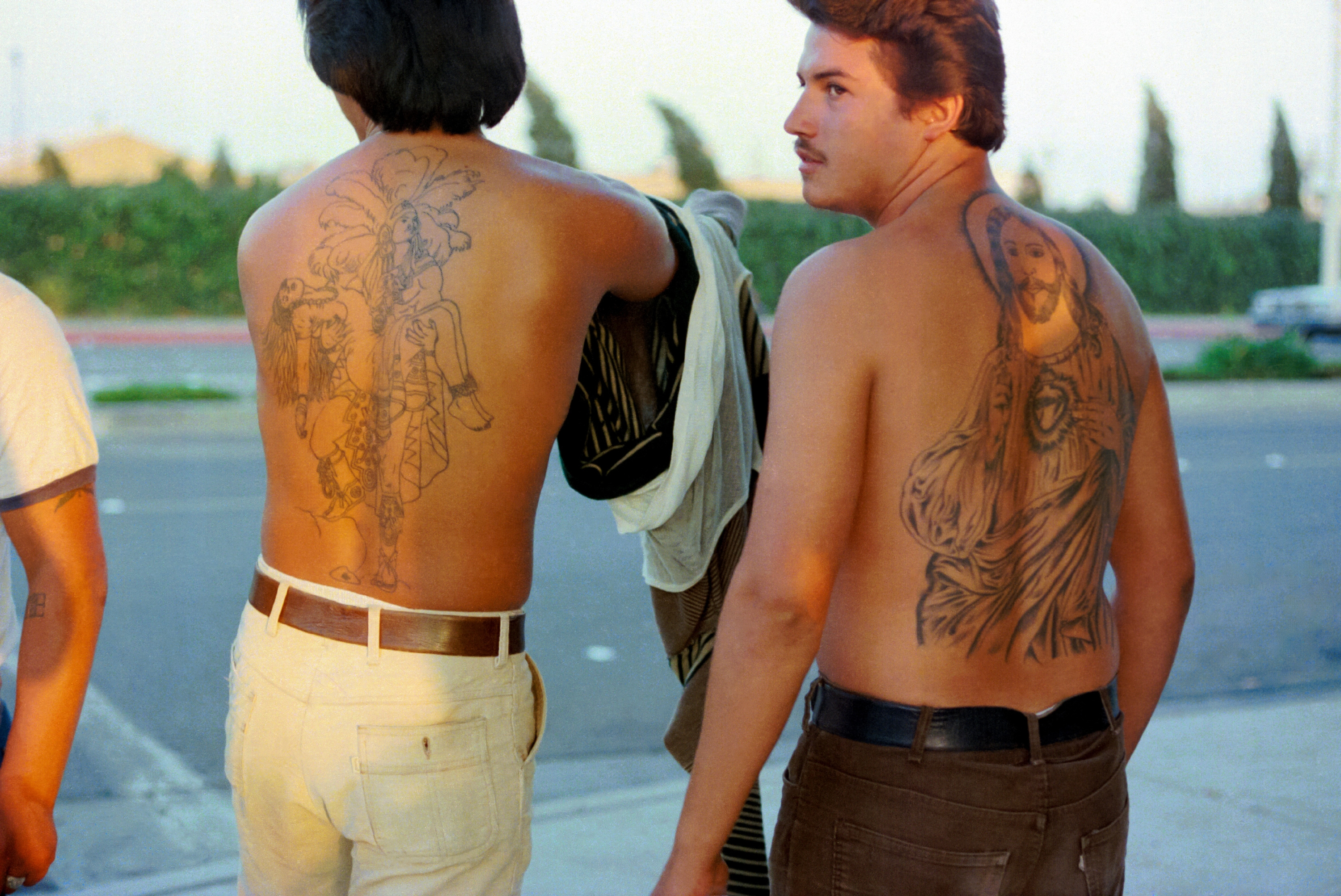

Valadez has worked in this city for over fifty years. A trailblazer of the early Chicano Arts Movement in 1970s-80s Los Angeles, he is a painter and muralist known for his photorealistic, dreamlike depictions of East LA. Less well known is his photography practice, which quietly developed alongside his painting career. Now a group of rare, mostly unseen images is on view at Luis De Jesus through December 20. A Two Second Gaze spans a 15-year stretch when Valadez had a studio on Broadway in downtown LA.

“I was very idealistic,” said Valadez of his earliest days making art. “I was gonna try to be an artist, a political artist…the self-awareness was about being Chicano. It was a social political awareness that we were Mexican and we were Americans, raised American with all that idealism…I was committed to being a Chicano artist, whatever that meant.”

He was always a realist, good at that hand-eye coordination kind of drawing. Between idealism and realism, his political awareness found its way: “ …to do a highly realistic, traditional drawing and painting of your community was kind of subversive.” At the time, realism belonged to the Western canon, a canon that made little room for Black, Chicano, or Asian American subjects, much less depicted them in a way that felt alive, complicated, or true. “So we started doing highly realistic portraits of our own people and our own environment in the urban centers.”

Valadez painted from pictures, and he needed source material. He tried magazines—nothing resembled the life he knew. “So we had to develop it ourselves. And so I picked up a camera—a friend of mine gave me a camera. I went through a series of cameras and I went through years of becoming a better photographer. But I wasn't trying to be a photographer.” The camera was like his sketchbook. He brought the photos back to his studio to recreate them on canvas, painting as many as seven photos together in one cinematic composition.

For decades, he did not think of these photographs as artworks on their own. That’s part of what makes A Two Second Gaze so compelling. In one moment, you see the photos as sketches or fragments of Valadez’s canvases. And in the next, the subjects step forward in their own right- looking at us with curiosity, an air of mischief, or the indifference of someone waiting for a bus. It was all in those two seconds for Valadez- the moments between focusing and shuttering the camera. “You become really self-aware," he said, "Of what you know, what you're doing, what people are doing." And the gaze he got in return: "It was inquisitive, like- was that guy taking my picture? Yeah. And then it’s like, why? So before it gets to the why you gotta snap it and those are the two seconds.” The everyday people of DTLA, poised to become artwork as soon as Valadez snapped the camera.

The photographs all have stories, per Valadez: these were people he saw on the streets around his studio every day. He got to know these subjects, less personally than as part of his urban landscape. There is one photo I cannot stop thinking about after leaving the exhibition: La Gran Estafa (1982).

A man in a clean suit and nice shoes, awkwardly crumpled on the sidewalk with a hand half-outstretched to Valadez’s lens. He looks at us straight-on with this soft but trepidatious expression. “ He was a beggar, and he would be out between the Million Dollar Theater and the mostly Spanish bookstore, then the Grand Central market was right nearby,” said Valadez. “He was double jointed, and I would see him every day…I didn’t know him personally, but I would see him, and I just caught him looking at me.” Valadez named the shot after the book title right above the man’s head: La Gran Estafa, The Big Fraud. The man’s half-squint expression, “the big fraud,” the suit still neatly pressed, a suggestion of performance—I still have so many questions. It is a fantastic photograph.

Together, along the gallery walls, these images offer a vivid account of walking the blocks of downtown Los Angeles in the 1970s. “The urban setting of Los Angeles in those years was really the center of my world,” Valadez said. “The intersection of cars and people and buildings—everything that was downtown.” He’d leave his Broadway studio and walk. “I wasn’t looking for a specific type of person. This is my environment. This is where I grew up. This is where I live… I wanted to be a good realist artist…but you know, I wanted to paint where I was from. It's gotta be the truth.”

With time, the city shifted—and so did he. A large mural commission required higher walls and more studio space, pulling him away from the intensity of downtown. Eventually he moved to Highland Park to start a family. Downtown had been engines, voices, horns, all those layered human sounds that stitched together his days in that studio. And then suddenly: quiet. “I'll never forget finally moving everything, getting out,” Valadez recalled when leaving Downtown LA really sunk in. “I remember going out into the backyard. And it was so quiet, you know, and [downtown] I used to wake up to the bus schedule at 6 o'clock in the morning. There were homeless people shouting and a lot of different stories. I mean, I could go on, but when I got here, I'm sitting out in the yard. We're at the bottom of Mount Washington. The San Raphael wraps around the top. And so I'm sitting here and I hear this roar like a train. And I go, what the hell is that? And it's the wind just coming through the ravine. I thought, wow, that's amazing.”

Around three years ago, Valadez went back to work in a studio downtown following an offer from the LA Theater Center: “You know, it's like I'm not downtown anymore…it was different. I'm kinda used to it now, but it's different. Or maybe I'm different, you know? For sure I'm different.” That difference—between then and now, between the two seconds snapping a photograph and the arc of a fifty year career as an LA artist—is what makes A Two Second Gaze so special. These photographs carry a tenderness toward a place that shaped the artist as much as he documented it. Valadez’s lens is personal and careful, filled with optimism and admiration for the downtown LA that was once his world.

Thank you very much for speaking with me, Hin and John—it was very special to meet you both.